Brent Cross

If there’s one word that stayed with me after walking the Brent Cross masterplan, it’s community.

Not in the abstract, policy-friendly sense but real, messy, energetic, people-led community. The kind that turns a derelict football pitch into a garden, a shed into a civic hub, and a temporary open space into the beating heart of a neighbourhood before the buildings even land.

Brent Cross Town is huge. One of the UK’s biggest regeneration schemes, it’s aiming to become Europe’s largest net zero development by 2030. 6,700 homes, a 25,000-strong future population, 50 acres of green space. The kind of numbers that sound impressive, but only tell part of the story.

What struck me on this visit was less the scale and more the sequencing, and the mindset. Open spaces were delivered first. The estate management company was up and running from day one. They didn’t wait until the end to invite public life in, they started with it. That feels like a quiet revolution in how these projects are typically approached.

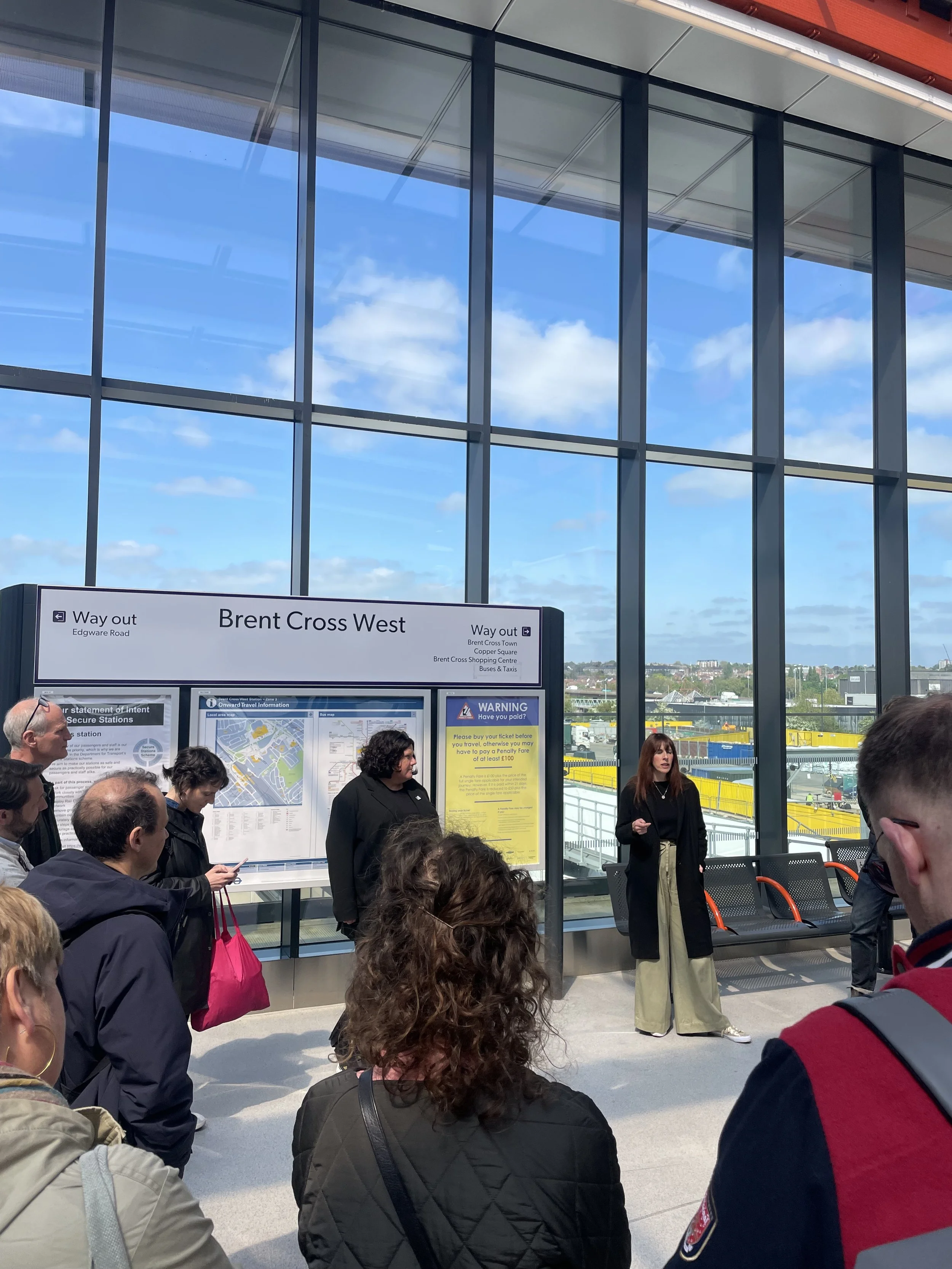

The new Thameslink station sets the tone: a genuine arrival point, linking what used to be a 40-minute walk apart. It opens up the site physically and symbolically, a connection, not just construction. But beyond infrastructure, the early green spaces have carried huge significance. Residents were understandably wary of losing the fields and informal play areas they already had. In response, the team created temporary green spaces during the pandemic, something immediate and quite generous, before committing to permanent, inclusive landscapes that include climbing walls, skate spots, and active edges. It’s hard to fake care like that. And you can feel it in the way the spaces are used.

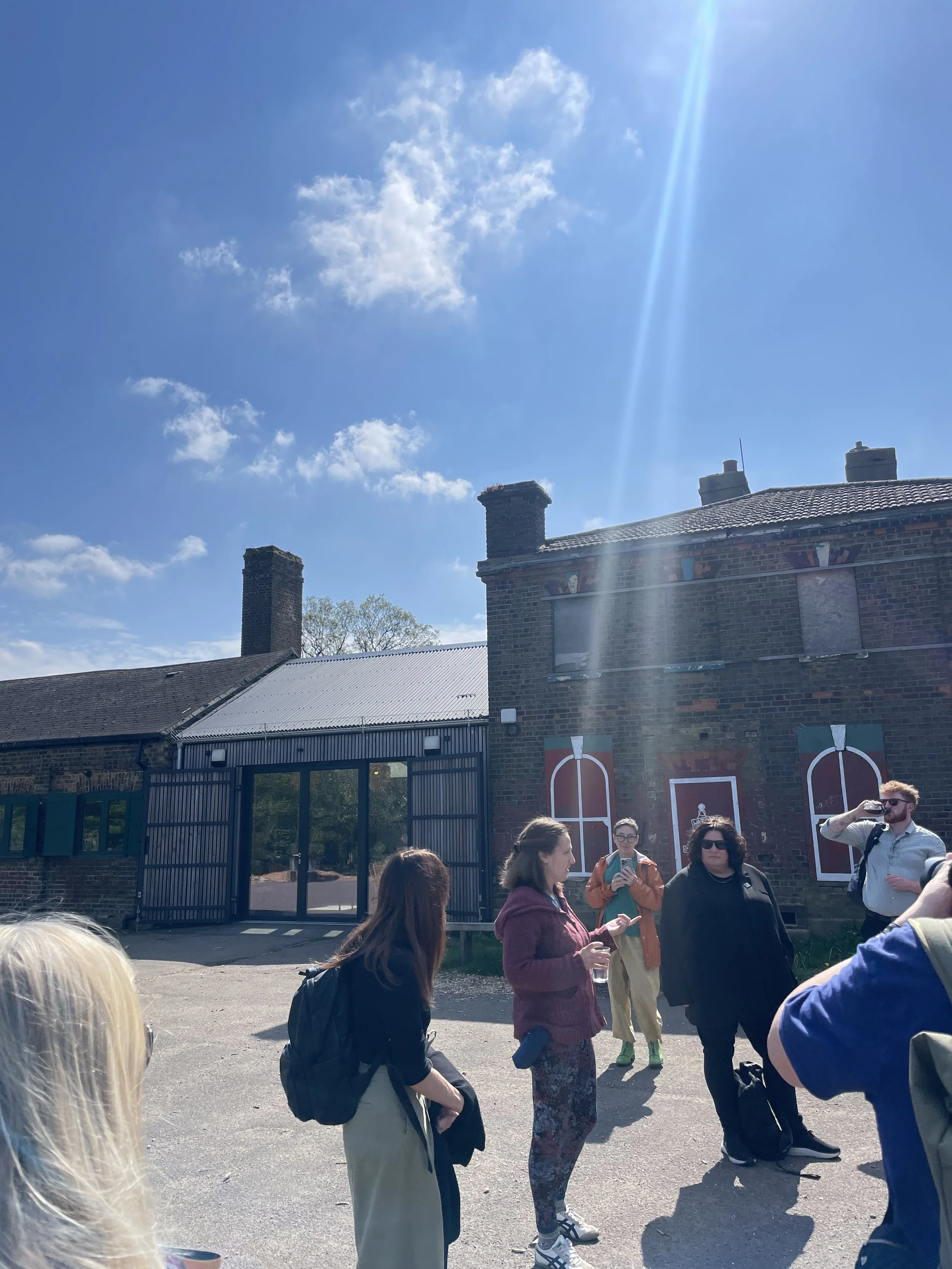

And then there’s the community story, which is where the heart of the place really is. Years ago, before the masterplan was fully in motion, a group of local people reclaimed a forgotten corner of land, a leftover football pitch that never got handed back. 12 people, with only a £10k grant, and a shed. That’s how it started. The first potter. The first baker. No glossy render, no formal brief, just human’s being, and creativity. Walks, yoga, pottery, food markets, cocktails, composting.

Something said that really stayed with me: “It wasn’t a deficit, it was potential.” That flips the whole regeneration narrative. They weren’t waiting to be saved. They already had what they needed to make something beautiful, they just needed the space and a bit of trust. It wasn’t about what was missing, but about what could grow. It’s also quite emotional, in a quiet way. To look at a derelict football pitch or a bit of scrubby land and see possibility, that’s an act of hope. It’s about seeing value where others might see waste.

Now that spirit lives on in a community-run café, Our Yard at Clitterhouse Farm, workshop and garden space, designed with friends from Central Saint Martins. It’s organic and evolving. That’s the model that unlocked the site’s identity, long before any masterplan arrived.

So when we heard the presentation about the high street typologies, Gort Scott’s very carefully studied, well considered study that draws learnings and guidelines from real high streets in London. I couldn’t help but wonder: what if the high street wasn’t just designed for the community, but by them? If the most vibrant, loved part of Brent Cross so far grew from a shed and a market stall, shouldn’t that be the blueprint for the town’s commercial core?

What if the high street was a lived-in layer of community energy, slow-grown, shaped by need and imagination? We talk a lot about retail ecosystems, but this one’s already alive. It started with 12 people and a shed. And how does the public realm reflect those different typologies and the community?

Meanwhile uses have played a big part, too, sports, arts, screenings, half-term activities. These weren’t afterthoughts, but the first building blocks of place. It was refreshing to hear how Manchester University worked with the team to study social value and wellbeing from the very beginning, creating a baseline before the design. Not just observing people, but inviting them in to shape what followed.

There’s more to come. Co-living, housing diversity, cultural programming. But walking Brent Cross reminded me that regeneration doesn’t start when the cranes arrive. It starts the moment someone looks at a patch of grass, or a broken bit of asphalt, and says: let’s do something here.